WAIMATE DISTRICT COUNCIL

SIRRL – What did Council know — and when?

Official Information Act (OIA) material shows that Waimate District Council (WDC) met with representatives connected to a waste-to-energy proposal later known as Project Kea on 16 June 2020 — around 15 months before the proposal was publicly announced.

Why was the community not told at that point that discussions were already underway?

Public awareness only followed a 15 September 2021 Stuff article titled “Waimate in the running for $350m energy plant.” In that article, Mayor Craig Rowley described the proposal as “exciting” and potentially beneficial for the district, while noting that it had not yet entered the consenting process.

If the project was still at an early stage, what information had Council already seen — and how had it shaped those early public comments?

Why was the first full briefing held behind closed doors?

On 28 July 2021, WDC Chief Executive Stuart Duncan invited Kevin Stratful of South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) to present Project Kea to a full Council meeting held in committee — meaning the public was excluded.

Why was this briefing not held in open session, given the scale and significance of the proposal?

What questions were asked by councillors — and what answers were provided — that the community never got to hear?

Following that presentation, WDC appointed staff member Michelle Jones as the primary point of contact for Project Kea.

Why was a dedicated council liaison established at this stage, before any public consultation or consent application?

Who was managing the message?

Before Project Kea was publicly announced, SIRRL engaged the public relations firm Convergence to help prepare communications, including a project website.

OIA correspondence shows Convergence:

asked Council staff to obtain a “statement of support” from the Mayor, and

requested a list of key local influencers.

Why was a private PR firm coordinating with council staff on messaging for a proposal that had not yet entered any statutory process?

A Zoom briefing later took place involving Mayor Rowley, Jones, and Jacqui Dean, using background material prepared by Convergence.

Was this briefing informational — or promotional?

And why was it necessary at this early stage?

What was the purpose of the “information sessions”?

SIRRL hosted public information sessions on 22 and 23 September 2021 at the Waimate Event Centre. These sessions promoted the waste-to-energy concept and indicated an intention to lodge a resource consent application later that year.

Yet:

limited technical detail was provided, and

no consent documentation was available for scrutiny.

Jones circulated an internal email inviting WDC staff to attend and advising that Mayor Rowley was acting as the spokesperson for Project Kea, with all media enquiries directed to him.

If the Mayor was not supporting the proposal, why was he positioned as its public spokesperson?

Council records show that the Mayor, Chief Executive, and councillors did not attend either information session.

Why not attend the only public opportunity to hear directly from the proponent — especially when councillors later said they had unanswered questions?

Councillors raised concerns — so what happened next?

After the July 2021 presentation, Councillor Fabia Fox emailed fellow councillors urging caution and stressing the need for a broader understanding of waste-to-energy impacts. She shared independent analysis on incineration to inform the discussion.

Councillor O’Connor responded by warning against being influenced by “soft-sell PR,” while remaining “optimistic but cautious.”

If councillors recognised the limits of the information they had received, why was no further open briefing requested?

Why were no councillors present at the company-run information sessions to test claims and ask hard questions directly?

Why these questions matter

Large, complex infrastructure proposals rely on public trust. That trust depends on:

transparency,

clear separation between promotion and process, and

elected representatives being visibly informed and engaged.

This record raises legitimate questions about how Project Kea was introduced, who shaped the narrative, and whether the community saw the same information — at the same time — as decision-makers.

Asking these questions is not about motive.

It is about ensuring that future decisions affecting Waimate are made in the open, with the community fully informed and involved.

Were private meetings held — and why were they denied?

On two separate occasions, Why Waste Waimate (WWW) asked Mayor Craig Rowley whether he had attended private meetings with representatives of the waste-to-energy proposal.

On both occasions, the Mayor categorically denied that any such meetings had taken place.

So why does OIA material tell a different story?

What do the records actually show?

Information released under the Official Information Act confirms that Stuart Duncan, Chief Executive of Waimate District Council (WDC), organised a meeting on 16 June 2020 involving:

Kevin Stratful (REL / South Island Resource Recovery Limited),

Paul Duder (Babbage Consultants),

Mayor Craig Rowley,

Stuart Duncan,

Michelle Jones, and

local Farmlands real estate agent Tim Meehan.

The meeting took place in Council chambers and carried the subject line:

“Catch-up meeting re: waste recovery proposal.”

If this was only an introduction, why was it described as a catch-up?

What had already occurred that required catching up?

And why was there a second meeting?

OIA material also confirms a second meeting, held on 19 May 2021 at the Waimate Event Centre, involving Duncan, Rowley, Stratful, and Duder. This meeting was organised by Jones.

Duncan later described this meeting as “a catch-up of where the proposal was currently.”

What progress was being reviewed at that point?

And why was this discussion again held outside public view?

Why don’t the official records show these meetings?

Neither of these meetings appears in:

the Mayor’s reported meetings, or

the Chief Executive’s reported meetings

that accompany Council minutes.

Without the OIA releases, no public record of these meetings would exist at all.

Why were meetings of this nature — involving the Mayor, CEO, and a major infrastructure proponent — not formally recorded?

Why were no notes taken?

WWW requested copies of any notes or minutes from both meetings.

The Chief Executive replied that no notes or minutes were taken.

Is it standard practice for meetings involving senior elected officials, council executives, and external proponents to proceed without any formal record?

How can accountability be assessed if no contemporaneous record exists?

Conflicting explanations

When asked about the purpose of the June 2020 meeting, Duncan stated it was simply to “make introductions.”

Yet the email subject line explicitly referred to a “catch-up meeting.”

Which explanation is correct?

Similarly, the May 2021 meeting was described as a progress update — again raising the question:

what level of engagement had already occurred by that stage?

What about the electricity-leveraging claims?

In the lead-up to the October 2022 local body elections, a council candidate alleged on social media that:

meetings had taken place between the Mayor, WDC representatives, and SIRRL / REL, and

those meetings included discussions about WDC leveraging 20% of the electricity generated by the proposed plant for resale to the community.

The candidate also claimed:

to have been present at several such meetings, and

that WDC staff had scribed those meetings.

Were these serious allegations simply election rhetoric — or did they warrant closer examination?

What was denied — and what was later acknowledged?

WWW asked Mayor Rowley whether:

such meetings had occurred, and

discussions about electricity-leveraging had taken place.

The Mayor denied both.

Deputy Mayor Sharyn Cain later commented publicly that she had asked both the Mayor and the Chief Executive about the alleged meetings, and that both denied they had occurred.

Yet at a meeting between Rowley, Jones, and WWW members on 14 August 2023, Jones acknowledged that:

several meetings had taken place, and

the individual who made the social media allegations was present at those meetings.

Why did it take nearly three years — and a direct meeting with community representatives — for this to be acknowledged?

What remains unresolved?

While both Jones and Rowley denied that discussions about electricity-leveraging occurred, the sequence of denials, partial acknowledgements, and absence of records leaves key questions unanswered:

Why were meetings repeatedly denied when OIA material later confirmed they occurred?

Why were none of these meetings formally recorded or reported?

How can the public assess what was — or was not — discussed?

These questions are not about intent.

They are about record-keeping, transparency, and trust — and whether the community was given the same visibility of events as those in positions of authority.

How has Council responded to concerns — and does that response stand up?

Throughout this process, Waimate District Council (WDC) has maintained that it acted appropriately and has declined to acknowledge any shortcomings in how it handled engagement with the Project Kea proposal.

But how consistent has Council’s own account been?

When questioned by Why Waste Waimate (WWW) and Deputy Mayor Sharyn Cain, both Mayor Craig Rowley and Chief Executive Stuart Duncan initially stated that no meetings had taken place with waste-to-energy proponents.

Those statements were later revised, with the Mayor acknowledging that meetings had, in fact, occurred.

Why did it take repeated questioning and OIA releases for this to be conceded?

And why were the initial responses so categorical?

Were notes taken — or not?

Council has consistently stated that no notes or minutes were taken at the meetings involving the Mayor, Chief Executive, and representatives of South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL).

However, an individual who was later acknowledged by both the Mayor and senior council staff as having been present at those meetings has stated that notes were taken.

Which account is correct?

If no notes exist, why does at least one participant recall them being recorded?

And if notes do exist, why have they not been released?

Why not resolve this with evidence?

That same individual also alleged that discussions took place about the Council leveraging 20% of the electricity generated by the proposed plant for resale back to the community.

Both the Mayor and the Chief Executive deny that such discussions occurred, implying that the allegation is unfounded.

But if no written record exists — how can this be verified either way?

Wouldn’t contemporaneous notes be the simplest way to confirm or dismiss such a claim?

Why weren’t these meetings formally reported?

It remains the case that none of the confirmed meetings with SIRRL representatives were recorded in:

the Mayor’s meeting reports, or

the Chief Executive’s meeting reports

that accompany Council minutes.

Why were meetings involving the Mayor, CEO, and a major infrastructure proponent not disclosed through standard reporting channels?

Is this consistent with good governance and transparency expectations?

What does Council’s own minutes now acknowledge?

An extract from the 15 August 2023 Council minutes states:

“In early September 2021, Council met with an executive officer from South Island Resource Recovery Ltd (this officer being Kevin Stratful). A meeting took place between the SIRRL officer, Council Mayor, and CE, where we were informed of the intention of SIRRL to explore the possibility of building a $350m waste to energy plant within the Waimate District.”

This statement appears to acknowledge:

a direct meeting between the Mayor, CEO, and SIRRL, and

early awareness of the scale and intent of the proposal.

Why does this acknowledgement only appear in Council minutes three years after the first meeting occurred?

How are community concerns characterised?

The same Council minutes go on to state that, over the preceding 18 months, Council had been subject to “regular social media claims of conflict of interest” and that:

“The main protagonist making these accusations against council has been a community group.”

Why are sustained, evidence-based questions from a community group framed primarily as social media accusations?

And why does Council state that such concerns are “not supported with any evidence” when:

meetings were initially denied but later acknowledged,

those meetings were not publicly reported, and

no records were kept?

What is the real issue here?

This is not about proving bad faith.

It is about whether Council’s explanations align with:

the documentary record,

later acknowledgements, and

basic expectations of transparency.

If Council is confident it acted impartially and appropriately, then why do:

timelines shift,

accounts change, and

records remain absent?

And why are these questions still unresolved years later?

What is missing — and why does it matter?

In the 15 August 2023 Council minutes, the Chief Executive Stuart Duncan refers to a “community group” as the “main protagonist.”

It is clear from context that this reference is to Why Waste Waimate (WWW).

Why characterise a community group asking formal questions — supported by OIA material — as a “protagonist”?

Does this framing fairly reflect the nature of the concerns being raised?

What meetings are left out of the official record?

The extract from the Council minutes summarises engagement with South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) as if it began with a meeting involving an executive officer in early September 2021.

But why does the record omit earlier meetings?

OIA material confirms that:

a meeting took place at Waimate District Council premises in June 2020, involving the Mayor, Chief Executive, senior council staff, a consultant from Babbage, and a local real estate agent; and

at least one further meeting occurred in May 2021, again involving senior council figures and the proponent.

Why are these meetings — which occurred more than a year before the full Council presentation — not acknowledged in the minutes?

Does summarising only later interactions give the public a complete picture of Council’s early involvement?

What does a “statement of support” signal?

OIA material shows that SIRRL’s public relations firm Convergence requested a supporting statement from Mayor Craig Rowley, and that such a statement was provided.

How should the public interpret a Mayor providing a statement requested by a proponent’s PR firm?

If the Mayor maintains he did not support the proposal, how does issuing a supporting statement align with that position?

And how does this sit alongside repeated assurances of impartiality?

Was SIRRL “invited” — and on what basis?

Council minutes refer to claims that Council “invited SIRRL into the district.”

WWW has asked a narrower and more specific question:

Why did Council invite SIRRL to pitch to a full Council meeting without first undertaking due diligence on the proponents?

The record shows that the Chief Executive formally invited Kevin Stratful to present to a full Council meeting on 28 July 2021.

Is that not, in practical terms, an invitation to present the proposal to elected members?

WWW has never claimed that Council invited SIRRL to locate in Waimate — so why is that distinction blurred in the minutes?

What did Council know about the site — and when?

There are also unresolved inconsistencies regarding Council’s prior knowledge of the proposed plant location.

The Mayor has repeatedly stated that he had no awareness of the proposed site location.

Yet the Chief Executive later told WWW that the company initially considered locating the plant on land owned by the Morven Domain Board, near the Morven township, adding:

“We talked them out of that one.”

How can Council talk a proponent out of a location without first knowing where that location is?

What do the documents show?

OIA material released later includes August 2021 correspondence between senior council staff and SIRRL representatives that explicitly acknowledges Morven as the proposed location.

This correspondence predates SIRRL’s public announcement of land acquisition in Morven by seven months.

Why was Council already discussing Morven as the site well before the public was told?

And why does this prior knowledge not appear in Council’s public narrative?

Why these gaps matter

This is not about accusing Council of wrongdoing.

It is about whether official records, public statements, and internal correspondence tell the same story.

When:

early meetings are omitted,

prior site knowledge is downplayed, and

community questions are reframed as accusations,

the result is confusion — and eroded trust.

If Council is confident in its process and impartiality, why not present the full timeline, clearly and consistently, and allow the public to assess it for themselves?

See council minutes extract below

Why was the Glenavy subdivision approved without notification?

The land near Glenavy, later identified as the proposed site for the waste-to-energy plant, was offered for sale by deadline treaty, closing in February 2022.

Shortly afterwards, Waimate District Council (WDC) received a resource consent application to subdivide 15 hectares from a much larger parcel of farmland.

Why was a subdivision of this scale progressing so quickly — and in isolation — given what Council already knew about the intended end use?

What information did Council rely on?

As part of the subdivision application, WDC relied on correspondence from Environment Canterbury (ECan) responding to a Council query about flood risk.

That response stated that:

the area sat within a low-risk flood zone, but

there was limited supporting documentation, and

local landowners may be able to provide further information about flooding in the area.

If ECan itself flagged that local knowledge might be relevant, why was no effort made to seek it?

Why was the application not notified?

In its decision to accept the subdivision application on a non-notified basis, WDC stated:

“The resource consent should be considered on a non-notified basis as Council was satisfied that the adverse effects of the activity on the environment would be no more than minor and, in terms of Section 95E of the RMA, no persons have been identified as being directly affected by the activity. Also, it is considered that there are no special circumstances requiring notification of the application.”

But how was Council satisfied that no persons were directly affected — when:

downstream landowners existed, and

ECan had explicitly suggested locals might hold relevant flood history?

What threshold was applied to determine that effects would be “no more than minor”?

Why wasn’t local flood history checked?

The subdivision consent was granted on 5 April 2022.

No consultation was undertaken with downstream landowners about flooding history, despite ECan’s advice that such information may exist.

Why was this advice not followed?

And how can flood risk be adequately assessed without engaging those most familiar with the land?

What changes were proposed to the site?

The proposed site includes an open water channel carrying surface water across the land from west to east.

The resource consent application lodged by South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) states that:

the water channel would be realigned, altering the natural watercourse; and

the ground level of the site would be raised to comply with building requirements in a flood-affected area.

How were the downstream effects of these changes assessed?

And what modelling, if any, was used to understand cumulative impacts?

Who might be affected by these changes?

Altering a natural watercourse and raising site elevation can change:

surface water flow paths,

flood behaviour, and

risks to neighbouring properties.

Given this, how can neighbouring landowners not be considered “directly affected”?

What did Council already know?

By the time the subdivision consent was considered:

senior Council staff had already discussed a forthcoming waste-to-energy proposal on multiple occasions, and

Council knew that a large industrial consent application was likely to follow.

If Council was aware that this subdivision was a precursor to a major infrastructure project, why was it assessed as a standalone, low-impact rural subdivision?

And why was the public not notified at a point where early scrutiny could still influence outcomes?

Why this matters

Subdivision decisions can lock in future land use pathways.

Approving a non-notified subdivision:

without local consultation,

with unresolved flood questions, and

in the context of a known future industrial proposal

raises important questions about process and foresight.

If the effects were truly minor, why was notification seen as unnecessary?

And if Council was confident in its assessment, why not invite public scrutiny at the earliest opportunity?

How was the Economic Development Steering Group formed — and how did it operate?

In 2019, Waimate District Council (WDC) established the Economic Development Steering Group (EDSG).

The group was initially proposed by Mayor Craig Rowley, with a structure of:

three elected councillors, and

three community representatives.

In February 2019, Council delegated the Mayor the authority to personally select the members of the EDSG.

Why was the membership not openly appointed or confirmed through a transparent process?

And what criteria were used to determine who would — and would not — sit on the group?

Who was appointed — and what roles did they hold?

Local businessman Ian Moore was appointed Chair of the EDSG.

WDC Chief Executive support manager Michelle Jones was appointed Group Manager.

The remaining members were:

Councillors Peter Collins, Jackie Guilford, and Miriam Morton;

local businesswoman Mandy Tagney; and

local dairy farmer Chris Paul, who is also the husband of WDC councillor Sheila Paul.

How were potential conflicts of interest identified and managed — particularly where close personal or governance relationships existed?

Why was an industrial sub-committee formed?

A smaller sub-committee was created to focus specifically on industrial park investigations.

This group consisted of:

Councillor Peter Collins,

Michelle Jones, and

Chris Paul.

Why was this work delegated to a small subset of the EDSG?

And how were its activities reported back to Council or the wider group?

What sites were considered — and how were decisions made?

OIA material shows that the EDSG investigated several potential industrial park locations, including:

council-owned land adjacent to the cemetery,

land near Knottingley Park,

council land on Gorge Road, and

reserve land at St Andrews.

All of these options were later set aside.

Why were these council-controlled sites dismissed?

And what assessment criteria were applied in reaching that decision?

Why did discussions shift to Fonterra land?

The EDSG ultimately pursued discussions with Fonterra about partnering to establish an industrial park on Fonterra-owned land at Studholme, adjacent to the Studholme Dairy Factory.

Those discussions involved:

EDSG member Chris Paul, and

Alan Maitland, Operations Manager at the Studholme dairy factory.

Notably, both Paul and Maitland were members of the Waimate Rotary Club.

Why were initial discussions about a major council-linked development taking place through informal networks rather than formal council processes?

Where did these discussions take place?

OIA material shows that:

some discussions between Paul and Maitland occurred at a Waimate Rotary Club meeting, not at Council offices; and

further discussions took place at Ian Moore’s Farmlands Real Estate Waimate premises, rather than in Council chambers.

Why were meetings about potential council–corporate partnerships occurring outside formal council settings?

Who else was involved — and why?

Those meetings also included Councillor Tom O’Connor.

Jones later stated that Councillor O’Connor attended several of these meetings, despite not holding any formal role within the EDSG.

Why was a councillor without an official mandate involved in these discussions?

And how was this participation authorised or recorded?

What was being asked of Council?

Notes from these meetings record that Alan Maitland requested that WDC prepare a proposal for him to take to Fonterra Head Office.

At that point:

had Council agreed in principle to pursuing this partnership?

was the wider Council aware such a proposal was being requested?

and was the public informed that Council resources were being used in this way?

Why this matters

Economic development groups can play an important role — but only when:

appointments are transparent,

discussions are properly recorded, and

informal networks do not substitute for public process.

When key conversations occur:

outside Council chambers,

without clear mandates, and

with limited visibility to the wider Council or public,

it raises legitimate questions about process, accountability, and governance.

If the EDSG’s work was sound, why not ensure its operations were clearly documented, openly reported, and subject to normal public scrutiny?

Were the industrial park plans and Project Kea really unrelated?

On 14 August 2023, members of Why Waste Waimate (WWW) met with Mayor Craig Rowley and WDC staff member Michelle Jones at Waimate District Council.

During that meeting, WWW asked a direct question:

Was there any connection between SIRRL’s waste-to-energy proposal and the Economic Development Steering Group’s (EDSG) work on identifying industrial park locations?

Why was this question important?

Because by June 2020 — and possibly earlier — SIRRL had already been engaging with WDC representatives, including Jones. At the same time, the EDSG was actively exploring industrial land options across the district.

Was this parallel timing purely coincidental?

What was said at the meeting?

Jones was asked whether the EDSG had discussed SIRRL’s intention to build a waste-to-energy plant and a potential associated business or industrial park.

Her response was clear:

“The EDSG hadn’t discussed it, as what SIRRL was proposing was heavy industry and what WDC was exploring was light industry.”

If that is correct, then why do the EDSG’s own records suggest otherwise?

What do the EDSG minutes actually show?

EDSG meeting minutes include multiple references to:

the “possibility of heavy industry development” adjacent to the Fonterra Studholme dairy factory; and

Studholme being described as a “good location for a heavy industrial park.”

How does this align with the assertion that the EDSG was focused only on light industry?

And if heavy industry was explicitly being discussed, how could a large-scale waste-to-energy facility fall entirely outside that scope?

What about partnering with Fonterra?

The July 2019 EDSG minutes also refer to the possibility of WDC partnering with Fonterra on an industrial park development at Studholme.

If the EDSG was already considering:

heavy industrial uses, and

partnerships with Fonterra at Studholme,

then how separate were those discussions from later conversations about major industrial proposals in the same area?

Why does this distinction matter?

If there truly was no overlap between:

early discussions with SIRRL, and

the EDSG’s industrial land investigations,

then the documentary record should clearly support that separation.

But when:

timelines overlap,

locations overlap, and

meeting minutes refer explicitly to heavy industry,

it raises a reasonable question:

Were these workstreams as distinct as later suggested?

What remains unanswered?

Why do EDSG minutes refer to heavy industry if only light industry was under consideration?

How were potential overlaps between industrial planning and SIRRL’s proposal identified and managed?

And why does Council’s verbal explanation differ from what is recorded in its own documents?

These are not allegations — they are questions about consistency, record-keeping, and clarity.

If Council is confident that no connection existed, why not place the full EDSG record alongside the Project Kea timeline and allow the public to see how those decisions developed in parallel?

Parallel tracks — or separate worlds?

At the same time that South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) was engaging with Waimate District Council (WDC) about a waste-to-energy proposal, WDC’s Economic Development Steering Group (EDSG) was actively exploring industrial park development opportunities across the district.

Same timeframe.

Same district.

Same senior council staff involved.

And yet, according to EDSG Manager Michelle Jones, SIRRL’s proposal was never discussed by the EDSG.

How is that possible?

What roles overlapped?

Jones was not only managing the EDSG. She later played a key role in assisting SIRRL with the public rollout of Project Kea, including coordination with its public relations firm.

If SIRRL was already engaging with Council — and Jones herself — while the EDSG was assessing industrial land options, how were potential overlaps identified and managed?

Or were they simply treated as unrelated?

What about the EDSG Chair?

As Chair of the EDSG, Ian Moore was directly involved in industrial park investigations, including discussions with Alan Maitland, Operations Manager at Fonterra’s Studholme dairy factory.

Those discussions did not always occur in formal council settings.

They took place:

at Moore’s Farmlands Real Estate business premises, and

through informal networks such as Waimate Rotary Club, of which Moore was a member.

Why were conversations about major industrial development pathways happening outside Council chambers?

Why does June 2020 matter?

A Farmlands Real Estate colleague of Moore was present at the June 2020 meeting between SIRRL representatives and senior WDC staff — a meeting that occurred more than a year before Project Kea was publicly announced.

How does that square with the claim that the SIRRL proposal was never discussed within the EDSG context?

Were these simply unrelated conversations — or were they parallel discussions that never formally intersected on paper?

Coincidence — or governance blind spot?

To accept that SIRRL’s proposal was never discussed by the EDSG requires accepting that:

senior council staff were dealing with SIRRL on a major industrial proposal,

the EDSG was exploring industrial park development at the same time,

the same people and networks appeared across both streams, and

no overlap was ever identified, discussed, or recorded.

Is that a credible governance outcome?

Or does it point to a structural blind spot — where informal discussions, overlapping roles, and parallel workstreams were never brought together in a transparent way?

Why this matters

Economic development planning does not occur in silos.

When:

industrial land is being scoped,

major industrial proponents are engaging with council, and

the same individuals appear across both processes,

the expectation is not separation — it is coordination, disclosure, and clear records.

If the EDSG truly never discussed SIRRL, why do so many people, places, and timelines intersect?

And if the processes were genuinely independent, why does that independence rely almost entirely on after-the-fact assurances rather than contemporaneous records?

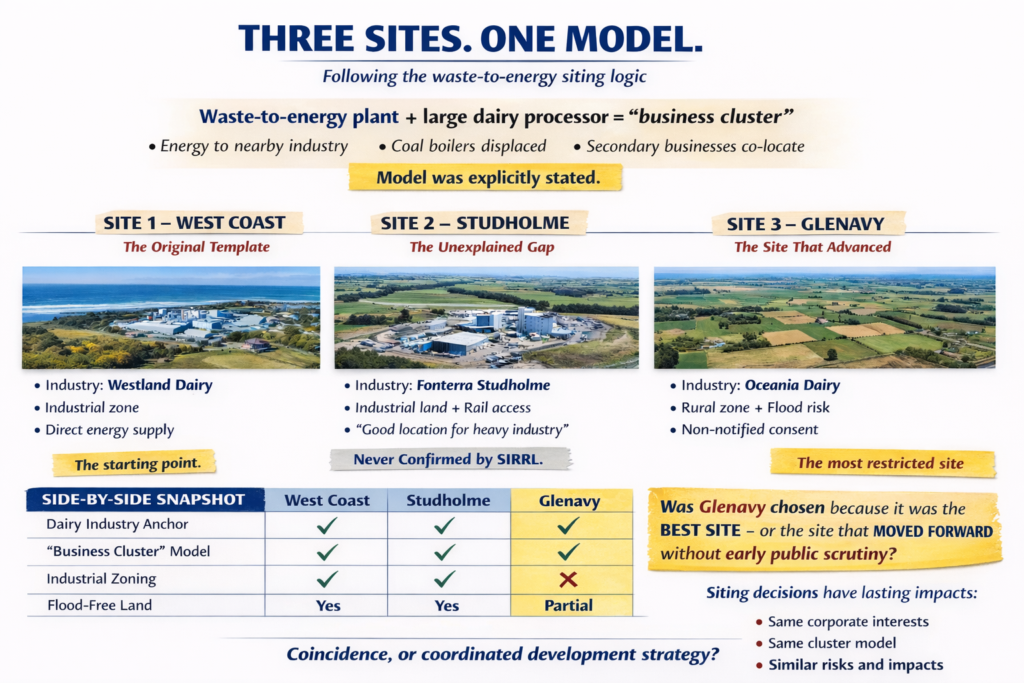

Was a “business cluster” always part of the plan?

When South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) publicly launched Project Kea, it stated that the plant would:

supply energy to neighbouring industries, and

attract businesses interested in relocating nearby to use that energy, creating what it described as a “business cluster.”

Why was the idea of a surrounding industrial cluster embedded in the proposal from the outset?

And how closely did that concept align with other industrial planning already underway in the district?

Now that the pathway is clear, the next graphic shows how the same ‘business cluster’ siting logic appears across three locations — West Coast, Studholme, and Glenavy.

Why Glenavy — and why near existing industry?

When SIRRL later announced the purchase of land at Glenavy, near Oceania Dairy, it again emphasised that the location was chosen to:

provide energy to nearby industry,

offset coal boilers, and

support the development of a business cluster.

This was not a new idea.

Earlier proposals by the same proponents on the West Coast had similarly sought to locate a waste-to-energy plant close to the Westland Dairy factory to supply energy directly to an adjacent industrial user.

Is proximity to large dairy processors a recurring siting strategy?

What about Studholme?

Given that:

SIRRL’s model relies on supplying energy to nearby industry, and

Waimate District Council (WDC)’s Economic Development Steering Group (EDSG) explored industrial development at Studholme, adjacent to Fonterra’s Studholme Dairy Factory,

is it reasonable to ask whether Studholme was examined as a potential location for Project Kea?

To date, SIRRL has not publicly stated whether Studholme was considered.

Yet on paper, Studholme appears to offer:

existing industrial zoning,

land outside flood-affected areas, and

better rail access for bulk freight movements.

If a business cluster was central to the proposal, why was a site with these characteristics not publicly discussed?

Are two conversations being blurred?

In a Timaru Herald letter to the editor, WDC Councillor Tom O’Connor referred to the SIRRL proposal as being located at Studholme.

However, in a Stuff article around the same period, SIRRL stated that it had purchased land at Glenavy.

Why the discrepancy?

Was this simply an error — or does it reflect how closely:

the industrial park discussions at Studholme, and

the waste-to-energy proposal

were sitting alongside one another in Council conversations?

Why does Councillor O’Connor’s role matter?

Councillor O’Connor had participated in industrial park discussions involving Alan Maitland of Fonterra — discussions that centred on Studholme.

If those discussions were running in parallel with awareness of SIRRL’s proposal, is it surprising that the two concepts might appear to overlap in public commentary?

And if they were truly separate, why does that separation appear unclear even to those directly involved?

Why this matters

The idea of a business cluster powered by a waste-to-energy plant sits at the intersection of:

industrial land planning,

energy strategy, and

major infrastructure siting.

When:

multiple industrial sites are being discussed,

similar proponents and energy models recur, and

public statements appear to conflate locations,

it raises a simple question:

Were these proposals evolving independently — or were they part of a broader, interconnected conversation that was never clearly articulated to the public?

Transparency matters most when plans are still forming.

If Studholme was never considered for Project Kea, why not say so plainly?

And if it was considered, why does it not appear in the public record?

EDSG Industrial park group: Timeline

Waimate District councillors approve 25-page draft plan – “Our District, Our Future” Waimate District Economic Development Strategy – and also approve the establishment of an economic development steering group made up of three elected officials and three community members.

Rowley said the steering group will form project teams to implement the action plans. “It’s critical that this has been and is a partnership with council and the community. I want this to be a 50/50 partnership between council and the community, I’m just proud of the way it has been done.”

High on the EDSG list; was to explore the establishment of an industrial park in the Waimate District.

Economic Development Steering Group have its inaugural meeting. Members include: Chairman Ian Moore, Chris Paul, Mandy Tangney, Cr Peter Collins, Cr Jackie Guilford, Cr Miriam Morton and Council’s Executive Support Manager Michelle Jones.

Industrial park project sub committee formed. Members include: Cr Peter Collins, Chris Paul and Michelle Jones.

July 11: Industrial park group meeting: Location: WDC chambers.

Attendees; Chris Paul, Cr Peter Collins, Michelle Jones. Visitor; Kevin Tiffen.

Notes from proposed industrial park Stage 2 options;

- Adjacent to Fonterrra

- Suitable for heavy industrial

- Chris to speak informally with Alan Maitland with a view to forming a partnership to develop an industrial park alongside Fonterra.

- State Highway access.

- Short distance to rail.

- Easy access to markets

- Fibre along SH1

- Business exposure

- NZTA approval

- Significant exposure for businesses

July 22: Industrial Park group meeting. Location: WDC chambers.

Attendees; Chris Paul, Cr Tom O’Connor, Michelle Jones. Apologies Cr Peter Collins.

Actions:

Chris to meet informally with Alan Maitland from Fonterra to discuss possible partnership.

Comments include:

- Need to make the industrial park more attractive to businesses/investors than what is currently available in Timaru and Oamaru. If the cost is cheaper, people are more likely to take a risk.

- Consider peppercorn rental, rates remission or other incentives for 5 years if a business signs up for a 25 year lease.

Notes in relation to industrial park:

August 5: Industrial park group meeting: Location WDC chambers.

Attendees; Chris Paul, Cr Tom O’Connor, Cr Peter Collins, Michelle Jones, Kevin Tiffen and Dan Mitchell.

Notes include;

- Ian and Chris spoke with Alan Maitland from Fonterra at Rotary last night. Alan is keen to discuss further when he returns to the Studholme site after 26 August.

- Alan would like to discuss ideas that he could submit to Fonterra Head Office.

Notes in relation to industrial park.

The project team met with Dan Mitchell and Kevin Tiffen to discuss the council owned Gorge road land as a potential site for light industry, and heavy industry on SH1 adjacent to Fonterra.

Chris to arrange a meeting with Alan Maitland from Fonterra.

October 7:

- Email from Chris Paul to Michelle Jones: “Hi I have arranged meeting with Alan Maitland, Fonterra. Meeting at 2:30pm Monday 7/10/2019.”

- Email from Karlyn Reid to Tom O’Connor: “Hi Tom, I phoned Chris Paul, the meeting is at Ian Moore’s Farmlands Real Estate office at 1:30pm.”

Michelle Jones initiates feasibility study for industrial park. Talks commence with Rationale to establish the viability of an industrial park in Waimate.

Rationale return with a quote of $30,000 plus GST and disbursements to complete the study.

July 11: EDSG meeting.

Notes relating to industrial park:

- The EDSG group agreed not to proceed with the Business park feasibility study on the basis that zoning for commercial and industrial land will be considered as part of the District Plan review; the proximity to large industrial parks in Timaru and Oamaru; and the availability of land if a business did want to expand or set up in the district.

- NOTE: April 2022; SIRRL publicly announce the conditional purchase of land to site the proposed plant at Glenavy. This news comes less than 3 months prior to Waimate District Council’s EDSG group abandoning plans to pursue industrial park explorations in the Waimate District.